The banking sector never seems to

stray too far from the headlines of the financial press. And there is good

reason for that. Financial companies occupy a unique nook in advanced economies

as they serve as the transmission mechanism to allocate capital…in the form of

excess savings…to its most effective use, which are investments offering the most

attractive risk/return profile. Therefore an undeniable link exists between a healthy

financial sector and overall economic well-being. In addition to this broader

function, investors shower the sector with attention given that, even after the

financial crisis, it remains the second largest bucket of the S&P 500.

Investments are not like the

entertainment industry, where any publicity is good publicity. Sector stalwarts

continue to get raked over the coals for missteps in the run up to the

financial crisis. Recent headlines involving one key player’s (Bank of America)

error in reporting capital data are reminders of that. Also the current

earnings season, as usual, has been front-loaded with banking announcements,

which, while varying among components, collectively hints at challenges to

top-line growth, especially in key business segments like fixed income and

mortgage origination.

This week it is particularly

relevant to examine the banking sector as the Dow Jones hit a record high and

Q1 GDP data came in at a comatose 0.1% annualized gain. Divining the health of banks can shed light on

the….ahem….logic underlying the equities rally as well as whether or not we can

expect GDP growth, which finally showed signs of life in H2 2013, to rebound

after this past winter of discontent.

An inflated market raises all ships….justified or not

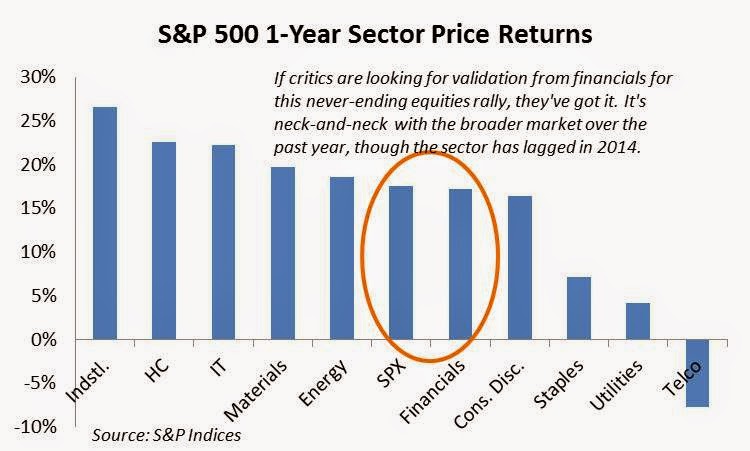

Investors love to say that equities

rallies need the validation of financial stocks. In the current instance, they’ve

got it….for the most part. Over the past year, excluding dividends, the

financial sector has gained a shade over 17%, only slightly below the 17.6%

registered by the S&P 500. For 2013,

financials actually outpaced the broader market, but have since come back to

Earth, being nearly flat year-to-date, while the S&P 500 is up over 1.5%.

Looking further back in time, one

can see the same story. Over one-year and three-year periods, on a total return

basis, financials have trailed the S&P 20.4% to 19.8% and 13.7% to 12.3%

respectively. Over a five-year timeframe, the delta is slightly larger with the

S&P’s annualized returns clocking in at 19% and financials, underperforming

at 16.9%. Over that length of time, two fewer percentage points makes a hefty

difference in total returns.

Of course the five-year returns encompass

the aftermath of the financial crisis, which includes the bounce-back year of

2010, making all the numbers appear a bit jazzier than they would otherwise. Since

then, the fact that financials have not joined more cyclical sectors like

industrials, consumer discretionary and IT in the upper echelon of returns can

be attributed to the regulatory constraints placed on the industry in the form

of higher capital cushions, the evisceration of their trading business and the

disappearance of the securitization cash cow.

Recent earnings reports from

leading banks tell this story. JP Morgan (JPM) saw its net income decrease and

Bank of America (BAC) recorded a net loss, in part due to litigation expenses

stemming from the housing crisis. The environment remains challenging for large

banks as every corporate treasurer and homeowner with a lick of common sense

has already refinanced, locking in historic low interest rates far out into the

future. So what had been a source of strength

in the early stages of the quantitative

easing era has become a shortcoming for both fixed-income divisions and

mortgage origination. Even Wells Fargo (WFC), which reported an increase in net

income of 14%, did so on the back of cost-cutting and not needing as many

reserves to cover loans previously considered suspect. Neither of those developments

can be relied upon for future growth.

Instead, what will be needed in coming

quarters is robust top-line growth and that can only come with an improving

economic outlook that entices bankers to lend out their considerable funds at a

substantially greater pace. Before jumping into that, we must ask the question whether

or not banking shares are attractively priced.

Discounted….perhaps for good reason

As seen below, based on estimated

full-year 2014 earnings, the nation’s five largest banks all have P/E ratios at

12.1 or under. These are at a discount to the 13.7 of the broader financial

sector (below) and dramatically lower than the 15.6 P/E ratio of the S&P

500. Banks are cheap on a Price to Book Value basis as well. But cheap does not

necessarily mean attractive. While the

sector as a whole has been aggressive in cleaning up the bad-debt mess from the

financial crisis…as opposed to European banks…one can see that some firms still

have lingering hangovers. Restrictions on dividends by authorities have

hampered growth of that previously alluring component of financial shares.

Prior to the financial crisis, when

financials were metaphorically printing money, unlike the Fed, which literally

printed it during multiple iterations of QE, investors were attracted to

banking shares, not just for their securitization-fueled growth model, but also

because it was the leading generator of dividends. And as we all know, the more

quickly a Board can return capital to shareholders, the lower the chance that

it goes off and funds some poorly thought-out acquisition (Countrywide comes to

mind). Even today, as seen above, the sector still contributes the second

greatest amount of dividends within the S&P 500. And this is with a

collective dividend yield of 1.8%, firmly in the lower rung of sectors (telco

is 5% and utilities are 3.8%). Imagine what financials could return if

regulators took their foot off of bankers’ throats?

Spring is here. Are the green shoots?

One cannot lay blame for the sector’s

woes entirely on its governmental overseers. After all, banks did take some

egregious liberties in their lending practices in the mid-2000s, which has

merited greater oversight. The other constraint hampering the sector is the

economy itself. Corporate borrowers don’t like uncertainty and will not

increase their fixed costs if future business prospects seem foggy at best. Even

if the economy gets a mulligan in Q1 due to a wretched winter, GDP growth has

still averaged a depressing 2% over the past 13 quarters. Similarly bankers

hesitate to lend in such environments for fear of getting stuck with a bunch of

dud loans. Ironically the same authorities that are encouraging banks to be

less parsimonious with their reserves are the same ones threatening to sue them

back to the Stone Age if their lending is deemed inappropriate or predatory…whatever

those mean.

With the exception of personal

consumption chiming in at 3% in Q1….evidently from brisk hot chocolate sales….the

remainder of the data was abysmal. Headline growth was 0.1%, which is one tick

from no growth. Nonresidential business investment dipped into negative

territory and housing fell off a cliff at -5.7%, following Q4 2013’s wretched

-7.9%. Yes some of that can be attributed to the cold, but higher mortgage

rates (albeit still low by historical standards), did not help matters.

We have previously argued the need

for the U.S. economy to rebalance

away from a reliance on consumption, which accounts for two-thirds of GDP.

Another favorite mantra is that residential construction should be a consequence

of a robust economy, not the source of it, as was the case prior to the crisis.

Resolution to those issues are years away however. In the here-and-now, the

economy needs robust consumption and a rebound in housing, which sends positive

reverberations through a range of other sectors. The problem is that, with a

weak jobs market, household formation has slowed to a crawl and in several regions

subdued wage gains impede the ability of

potential buyers to move upmarket from starter homes.

There are signs of optimism. As

seen in the confusingly squiggly lines below, lending standards for commercial

& industrial (C&I), auto, and general consumer loans have gradually

loosened over the past two years. Demand has also picked up for these loans to

meet this newfound supply. The sole exception has been mortgage demand, which

has taken a nosedive as rates have risen and cash investors have satiated

themselves after gorging on the market for years.

This thawing of the lending market

can be seen in the return to growth of outstanding loans. While C&I loan

expansion has been impressive over the past few quarters, growth in consumer

and real estate loans remains well below pre-crisis levels. As noted above,

these two areas have been major contributors to GDP growth over the past few

decades and additional credit flowing into them will be necessary in order to

increase the trajectory of what has been a frustratingly tepid recovery. On a

brighter note, the growth in C&I loans likely represents credit flowing to

small businesses…ones too small to tap the hyperactive bond market….which is

important given the role smaller firms play in creating jobs in the United

States.

A rightful place in the portfolio? Better than tulips.

So it’s all connected. Optimistic

banks, willing to lend, provide a needed catalyst in a highly-levered…euphemism

for debt-addicted…advanced

economy. A healthy economy further

instills the confidence of bankers and also rewards investors by juicing the

profits of financial firms. Somewhere in here there is a story about the wealth

effect and virtuous circles but it is 1:00 AM and my double espresso has

finally worn off, so we best not go down that path.

Should one own banking shares

today? At current valuations, why not? At the very least they help diversify

one’s portfolio, are naturally levered investments and many listings are still

sources of attractive dividends. Given the new regulatory hurdles of the

gargantuan Dodd-Frank law and the tepid pace of economic growth, especially in

debt-dependent sectors, there is probably not much room for upside. This is

especially true if one is of the belief that the rationale of this extended bull

market is tenuous at best.

Not to go totally macro but much depends upon the interest

rate environment and how the Fed shimmies out of its extraordinary monetary

policy. If one believes that the Fed will back off any threat to raise the Fed

Funds rate thus keeping short-term notes tethered to the sub 1% range, and that

excess liquidity (or a return respectable growth) will light the inflation

flame causing a sell-off in longer-dated treasuries, the ensuing bear-steepening of the yield curve will

be manna from heaven for banking net-interest margins. Conversely, if the Fed indeed

raises rates while growth prospects remain muted, the consequent bear flattening would squeeze margins

while at the same time discourage lending in the slow growth environment. Two divergent

scenarios; a question investors and committees must hypothesize over in coming

weeks.

No comments:

Post a Comment